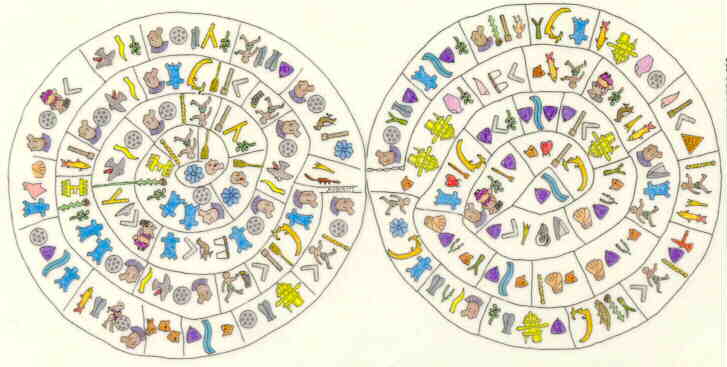

The famous spiral disk found in Phaistos, Crete in 1908 has long defied efforts to translate it or even to identify the language in which it is written or what kind of a document it might be (it is here in color to aid analysis). Though many scholars and amateurs have proposed theories and even translations, none has seemed persuasive to the great majority of observers. A skeptical view holds that the disk is a forgery, but most scholars reject this. Many scholars agree that the small sample of language in the disk makes a breakthrough very unlikely unless and until other samples of the writing are found.

The famous spiral disk found in Phaistos, Crete in 1908 has long defied efforts to translate it or even to identify the language in which it is written or what kind of a document it might be (it is here in color to aid analysis). Though many scholars and amateurs have proposed theories and even translations, none has seemed persuasive to the great majority of observers. A skeptical view holds that the disk is a forgery, but most scholars reject this. Many scholars agree that the small sample of language in the disk makes a breakthrough very unlikely unless and until other samples of the writing are found.

Many Germans have earnestly sought to overcome the Nazi past by publicizing its depredations, by acknowledging wrongdoing, by seeking restitution of stolen property, and by maintaining a respectful, responsive stance toward Jews in general and Israel in particular. Still, such is the burden of the Holocaust that another approach may also prove attractive to certain Germans. It involves Yiddish.

Many Germans have earnestly sought to overcome the Nazi past by publicizing its depredations, by acknowledging wrongdoing, by seeking restitution of stolen property, and by maintaining a respectful, responsive stance toward Jews in general and Israel in particular. Still, such is the burden of the Holocaust that another approach may also prove attractive to certain Germans. It involves Yiddish.

While Yiddish contains elements of Hebrew and Slavic languages, it is mainly an old dialect of German. A German speaker can understand most of it, and in fact Yiddish forms part of the study of German linguistics and literature, correctly understood. This means that a simple initiative could help bring Germans and Jews closer.