Carroll Quigley (1910-1977) was a noted historian, polymath, and theorist of the evolution of civilizations.

Carroll Quigley (1910-1977) was a noted historian, polymath, and theorist of the evolution of civilizations.

Born and raised in Boston, Quigley planned to pursue a career in biochemistry. But he soon shifted to history, to which he brought an analytical, scientific approach and a questing spirit. After receiving a B.A., M.A., and Ph.D in history from Harvard University,1 he taught at Princeton and Harvard. In 1941 Quigley joined the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, where he came to teach a highly regarded course, “Development of Civilization”.

Endowed with a Napoleonic constitution and willing to work 16 hours a day, Quigley was a rapid, retentive reader who devoured the contents of thousands of books and came to possess an exceptional range of knowledge in many fields. Not one to hide his light under a bushel basket, he claimed to have read everything worth reading. Fields of special expertise included aspects of prehistoric culture (e.g., primitive poison fishhooks), the impact of weapons technology on social organization, and the Anglo-American elite.

Quigley emphasized “inclusive diversity” as a value of Western Civilization long before diversity became a commonplace, and he denounced Platonic doctrines as an especially pernicious deviation from this ideal. Quigley argued that the reintroduction of Aristotle’s teachings in the Middle Ages, most notably in the work of Thomas Aquinas, led Western Civilization away from Platonism and onto the track of a highly fruitful approach to knowledge based on scientific observation and experimentation, and driven by ethical concerns.

As a spell-binding lecturer, Quigley made a strong impression on many of his students, including future President Bill Clinton, who referred to Quigley in his acceptance speech at the 1992 Democratic National Convention, saying:

“As a teenager, I heard John Kennedy’s summons to citizenship. And then, as a student at Georgetown, I heard that call clarified by a professor named Carroll Quigley, who said to us that America was the greatest Nation in history because our people had always believed in two things—that tomorrow can be better than today and that every one of us has a personal moral responsibility to make it so.”

According to Clinton’s biographers, he developed a relationship with Quigley and considered him his guru. During his presidency, Clinton made no mention of Quigley in public but was said to refer to him repeatedly inside the White House. At times Clinton also used Quigley’s concepts and formulations without attribution in impromptu remarks that enhanced his reputation as a thinker. When after his time in office he once listed his three favorite Georgetown teachers, however, Quigley was not one of them. Was Clinton hiding his deep indebtedness to Quigley for fear that people would (however unfairly) view him as a mere epigone of his revered mentor? Or did Clinton distance himself from Quigley because he believed derogatory rumors about his one-time guru (see below)?

In the 1950s Quigley did some consulting for the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, the Smithsonian Institution, and the House Select Committee on Astronautics and Space Exploration. He became a sought-after lecturer but was little involved in other kinds of consulting. Quigley served as a book reviewer for the Washington Star and was a contributor to and editorial board member of Current History. He was married and had two sons.

Quigley authored two influential books: The Evolution of Civilizations (1961) and Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (1966). Two other books were published posthumously from his manuscripts: The Anglo-American Establishment (1981) and Weapons Systems and Political Stability, a History (1983). Quigley’s efforts to have Tragedy and Hope reprinted by Macmillan were thwarted in a manner that led him to write that certain powerful interests were seeking to suppress him or at least his book. In fact, the book sharply criticized various individuals and groups, most pointedly the U.S. Air Force and the associated military-industrial complex, so his suspicion may well have been warranted.

A Flow of Concepts

Although he received only limited public and professional recognition for his contributions, Quigley was in fact a leading theorist of the rise and fall of civilizations, developing a 7-stage model (Mixture, Gestation, Expansion, Age of Conflict, Universal Empire, Decay, and Invasion) that was integrated into a framework of analysis that included dimensions of power (military and political), wealth (economic and social), and outlook (intellectual and religious). His illuminating discussion of the geographical and climatic matrix in which a civilization develops and his analysis of the mechanisms of expansion and conflict stages of civilization were a good deal more scientific and well-grounded than the more literary efforts of previous historians of civilizations. Many observers consider his to be the single best theory of the rise and fall of civilizations.

The penetration of Quigley’s analytical mind, his flow of novel concepts, his penchant for provocative formulations, his ceaseless crossing of disciplinary boundaries, and his willingness to challenge specialists and powerful groups in blunt and at times caustic language led to a fair amount of controversy, though in fact his political and social views were moderate. Quigley was an early and fierce critic of the Vietnam War; and he inveighed against the activities of the military-industrial complex that he thought were threatening to transform the United States into an empire, thereby dooming it to eventual corruption, fossilization, and decline. He was ever on the alert for signs of the processes by which a dynamic “instrument” of society that satisfied the needs of individuals could turn into a stagnant, self-aggrandizing “institution”.

A central concern of Quigley was whether Western Civilization could renew its best traditions—including investing in innovation and emphasizing spiritual values and interpersonal relations rather than material things—after the Age of Conflict between 1895 and 1945, or whether it would slide into an era of Universal Empire.2 Initially full of hope on this subject, he grew more pessimistic about it in his later years. Quigley said of himself that he was a conservative defending the liberal tradition of the West.

Conspiracies

Quigley became well known among those who believe that there is an international conspiracy to bring about a one-world government. In Tragedy and Hope, he based his analysis on his research in the papers of the Anglo-American elite that, he held, secretly sought to set the policies of the U.S. and UK governments through a series of Round Table groups. The Round Table group in the United States was the Council on Foreign Relations, connected with the J.P. Morgan banking cluster. He argued that before 1950 the Republican and (less so) Democratic parties were controlled by an “international Anglophile network” that shaped elections, though he also pointed out how the unrealistic thinking of some people in this network contributed to appeasement of Hitler, while in general the Round Table was less capable of influencing world developments than it aspired to be.

In particular, Quigley wrote that the J.P. Morgan group had funded communists along with other groups. Some 30 pages from Tragedy and Hope were incorporated into a short book titled The Naked Capitalist by Cleon Skousen, a right wing conspiracy theorist who claimed that Quigley was an Anglo-American elite insider who had revealed the elite’s support of communist subversion. Eventually Skousen had his book inserted into the Congressional Record. A bitter controversy took place at Brigham Young University and in the Mormon Church in which Skousen’s interpretation of Quigley was shown to be twisted and full of errors.3

Even as conspiracy theorists assailed Quigley for his approval of the goals (not the tactics) of the Anglo-American elite, they selectively used his information and analysis as evidence for their views. Quigley himself thought that the influence of the Anglo-American elite had waned after World War II and that, in American society after 1965, the problem was that no elite was in charge and acting responsibly.

No matter how reasonable Quigley’s thinking on this and other subjects was, the association of his findings with the kooky, paranoid fantasies of right wing conspiracy theorists, in combination with the sheer originality of his ideas and his drive to find and articulate underlying patterns, caused rumors to circulate about his mental status. His detractors, including jealous colleagues, an ambitious dean, and various enemies, were quick to fault him and continued to denigrate him for decades after his death, while he and his contributions were, with few exceptions, ignored by historians and the media. In addition, toward the end of his Georgetown career, Quigley ran into criticism from students unhappy about his grading (he was an old-fashioned grader), was roughed up in class by student protesters, and gave up his “Development of Civilization” course because an academic power game had attached unacceptable conditions to it. He became more distrustful, at times deeply so. In particular, he found it hard to shrug off the obsessive delusory thinking and hostility of the conspiracy theorists, which led him, for instance, to underperform in an interview about conspiracy theories.4 Still, Quigley remained a formidable thinker. He continued to espouse an optimistic vision of the potential of humankind and of the liberal values of Western Civilization. Eventually he retired to work on his book manuscripts. He died of a heart attack at 67.

Nowadays, Quigley is often spoken of in reference to his writings about the Anglo-American Establishment or as an influence on Clinton. But his theory of the evolution of civilizations, his methods of thinking, his multitudinous concepts, and his philosophy of social good have much more general and enduring importance. Among other things, they provide a valuable framework for understanding the interaction of civilizations in a global era as well as pointing out pathways to the future for Western Civilization. In addition, Quigley’s teachings and his dynamic persona had an impact on thousands of students and intellectuals, with outcomes that we are not yet in a position fully to assess.

*****

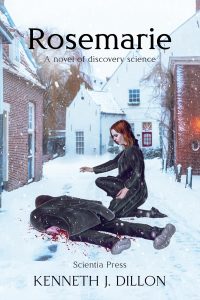

Kenneth J. Dillon is an historian who writes on science, medicine, and history. See the biosketch at About Us and his novel Rosemarie (Washington, D.C.: Scientia Press, 2021).